The Elusive Eagle: Charles McGill and the Anti-Trope By Joe Lewis

“Golf is a chronic and progressive illness. Once afflicted, all bets are off. You can bet the farm on that!” Anonymous circa 2016

Classically trained in the figurative painting tradition, a superb draftsperson, colorist and writer with the gift of gab, Charles McGill is an artist’s artist. Formal preparation gave him entrée to the history of art with extensive vascular connections to the High Renaissance, Dada, Futurism, Modernism and ethnocentric contemporary practices. With a well-stocked investigative toolkit, his ability to wield said implements with aesthetic prowess is immediately evident when observing how he handles relationships between materials, content and form. Something else becomes apparent as the viewer joins his trudge through difficult subject matter. Regardless of the complexity or darkness of his revelations, McGill never loses sight of beauty and craft – it’s what makes his work readily accessible on multiple levels simultaneously.

Ironically, though steeped within the fluid frame of race and representation, his initial adoption of golfing paraphernalia as signifier and manufactured agency had little to do with a quest for social commentary’s sweet spot. A devoted golfer himself, McGill’s foray into the sport’s hierarchical world began in a serendipitous moment, when he visited a gallery on his way to the links and someone said, “Do you mind if I take a picture of you? I’ve never seen golf clubs in an art gallery before.” McGill then realized the fertile possibilities of taking his love of the sport into the studio.

Before that encounter, McGill made a few aerial view, oil stick drawings of golf courses. They anchor his visual interest in the game and especially its baggage as possible subject and pallet. These early expressionist pictures, reminiscent of Kandinsky’s elaborate improvisational compositions, carve a semi-figurative way of looking at the physical terrain. You can feel him dragging his percolating critical discourse over the fairway, stripping it down to its most essential elements while connecting his well-honed figurative training to an exigent abstract urge that foreshadows his future dissection of the game and its components.

These abstractions would soon thrust through the “back nine to the frontline,” and eventually usurp the didactic tropes of image/text, the figure, race and commodification, embracing purity and immensity – the sweeping expanse of abstraction. It’s difficult to fathom how one finds beauty through the lens of exclusion, but McGill gives both original and meaningful life in spite of their metaphysical opposition.

The 1999-2000 exhibition Club Negro is an excellent introduction to McGill’s broad theoretical reach. Mercantilism sets the exhibit’s tone. Dreadlocked balls and clubs, lynching images and comparisons between lynching mobs and tournament viewing galleries provide the backdrop for McGill’s confrontation of stereotypical, often unspoken thoughts that color and shape the dark recesses of the collective racist consciousness. Another seminal work from that period not included in this exhibition, I am, I am not (1999), consists of 54 single balls on tees that are tightly packed together in a rectangular case with the following handwritten declarations:

My name was never Uncle Tom.

I have never been a runaway slave.

I have never used a hot comb.

I have never been an invisible man.

I have never had a dream.

I have never done anything by any means necessary.

The message slices into the room like a serrated monolith. McGill’s neo-conceptual quips are similar in depth and breadth to Jenny Holzer’s Truisms (1977-present), her Survival series (1983-1985) in particular, with two caveats. Both question the underpinnings of contemporary life in oracular fashion, but Holzer scratches its back while McGill’s machinations suck the marrow out of it. His are not political statements, but moral ones.

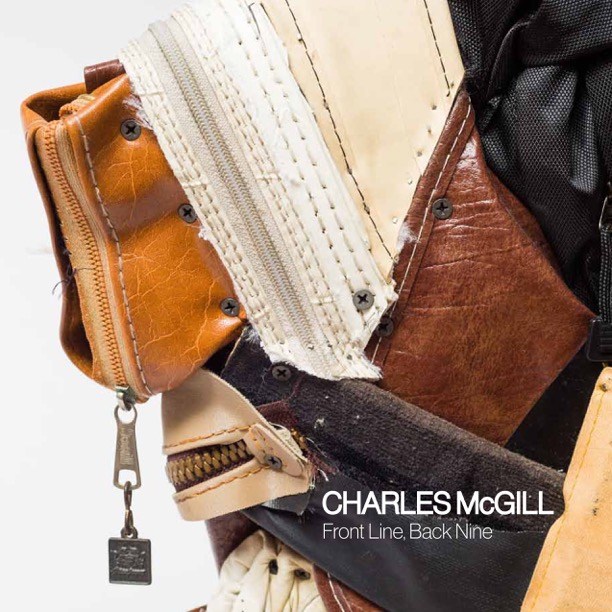

Club Negro’s blunderbuss read on social class, privilege, place and race created a praetorian plinth for McGill’s first collaged bag. Lynch Bag (1999) explores the deeply flawed nature of master-race civilization by mining historic lynching images, past and present, and coupling their shared DNA of Black objectification by decoupaging on a vintage leather golf bag. The decoupage process is labor intensive. It’s an amalgamation of cut images cemented together to form intricate designs and is thought to have originated in East Siberian tomb art, where Nomadic tribes decorated graves of their deceased with felt cutouts. As the practice expanded outward throughout the ancient world, it became more decorative and eventually a staple form of embellishment in both Asian and European royal courts. In its initial presentation, Lynch Bag was hung from the ceiling, like a floating tomb. For McGill, no symbiotic relationship is left to chance. And so, at that moment, he begins his long and tempestuous relationship with the golf bag.

The collage practice does not stray far from McGill’s formal training as a figurative painter but, in fact, solidifies his interest in redefining the human form. The layering, working with identifiable images, building relationships and surfaces based on color, form and rhythm is, as he has said, “painting without pigment.” The golf bag, its potbelly and occasional protruding booty, especially when fully clubbed, has a structural similarity to a human figure in stasis. When used as an allusion, it brings him full circle back to his roots, underscoring the emotional realness of his musings.

Over the years, his Baggage series (1999-2010) has morphed in three stages: decorative surfacing, figurative conglomerations and total reconstructions. His compositional formulas and critical extrapolations insert his practice into a long and storied tradition of artists who have born the responsibility and weight of cultural illumination. Their perpetual repurposing chases the mutating American racial pathology. Though not as decorative, the political intensity of the illustrations in Sue Coe’s How to Commit Suicide in South Africa (1984), that traces the history of apartheid, immediately comes to mind, as do Jacob Lawrence’s very shadowy War Series (1946-1947), a series paintings that juxtapose composition, form and perilous subtext.

McGill often returns to the figure. When he does, he takes no prisoners; It’s in his blood. His aggregate bag compositions, Night of Mischief (2012), and Fortress of Four (2015), stand guard like hooded, blinged-out stele in front of some secret society’s hideout or boundary markers establishing lines that shout; once crossed, it’s impossible to return. Bathed in the muted tones of a restricted palette, they channel the brute political anatomies of Philip Guston’s use of KKK imagery. Similarly, another group of distant relatives is the anti-war activist Leon Golub’s White Squad (1987), a series that codifies the arrest and interrogation of innocents by police or vigilante forces.

McGill’s unapologetic figures stand tall. Their cut, twisted, torn and screwed surfaces charge into one’s personal space with abandon and, like Civil War Night Riders, their disregard for humanity tries to redefine communities. Situated in the painful enclave of systemic inequality, they peer into the steaming caldron of history repeating itself – silently chanting, casting spells, and marking their territories.

McGill’s full body cast, Arthur Negro II (2007-2010), the multi-site performance, Playing Through (1998-2009) and the emergence of The Former Black Militant Golf and Country Club (1997) create a powerful nexus for McGill’s maturing oeuvre, a culminating treatise. The argyle-clad, life-size portrait of the infamous Black Militant power broker and founder of “The Former Black Militant Golf and Country Club,” Arthur Negro contemplates, with his heroic gaze, a future devoid of “the struggle,” and plenty of prime “tee” time – somewhere off in the distance. But just in case, his beret is cocked to the side, an indication of being down and ready for a fight. And, he is well-armed.

McGill assumed this persona in the performance work Playing Through. On a few different occasions, he took to the streets of Harlem, Tribeca and Hanoi. Peppering the gathering crowds with messages of revolution, he teaches putting techniques to passersby using the broad boulevards of 125th street, MLK Blvd. and in some instances, vacant lots as fairways and greens. The performance cadence is unmistakably Black, and it’s our first full on glimpse of McGill’s acerbic humor as he reads from Malcolm X’s speech, “After the Bombing,” on a bullhorn, and then sets up his next shot, teeing off watermelons.

Much like Da Vinci’s notebook drawings of the human body, McGill dissects the once segregated cultural, social and commercial enterprise of golf. Unlike Da Vinci, instead of using his research to inform the creation of an ideal body, possibly in search of a Pygmalion event, the performance codex is his final nod to the figure, as we know it. From this point forward, his work is primarily abstract in nature but still saturated with subtle societal innuendos of control and submission, personified by McGill’s savaging leather golf bags, crushing them, making them do things they don’t want to do. Whereas the majority of his previous constructions and objects were assemblage based and read well from ground level, he now positions himself at 10,000 feet, turning his micro post-conceptual-structuralism (class, race, representation, control and subjugation) into the macro (purity and immensity).

The PGA was the last major sport to integrate. How’s that for a construct? McGill’s initial foray into abstraction, in some undefinable way, lifts the opaque veil of the post-racial illusion from the present. His abandoning of the figure was counter-intuitive, especially when considering his training. He just ran out of room for it, and the embedded academic historiography. He likens the struggle to release himself from the bonds of the Age of Enlightenment’s darkest corners – a rationale for slavery, based on a hierarchy of races – like this, “it’s like sneaking up on a wild boar in the woods and trying to skin it while it’s still alive.” In a subtextual way, he begs the question, does the figure belong in 21st-century sculpture, when its origins represent the disintegration of reason?

It’s becoming increasingly apparent; the twenty-first century is a time of the minority majority – preparing for a new dominant culture constructed by and for them. McGill’s deeper incursions into abstraction, his skins, keep us tethered to an analog reality rather than fictive value systems distributed by the hegemonic capacity of capitalism.

Although some of his earliest non-representational pieces appear related to John Chamberlain’s fused and twisted monumental shapes, they are not. On the contrary, aside from their instinctual fabrication, their intent could not be further from each other. Unlike Chamberlain’s focus on cheap materials and junk sans political comment, and more akin to Melvin Edwards’ Lynching Fragments (1960s-present), McGill’s bailiwick reveals the severe fracture and dystopian agony of a society trying to survive while stretched and warped over a utopian iconographical reality. Indelibly shaped by notions of racial tension and segregation, they are removed performances, communing with the past, counting the moments while a self-defined cultural elite, trying everything it can to stay on top, implodes as a metaphor.