Read it a little more clearly:

THOSE AFRICANS LOOK LIKE WHITE ELEPHANTS: An Interview with Robert Colescott

By Joe Lewis

The humor is the bait. It is the price you pay to get in. Robert Colescott’s paintings deal with popular ballads that have been thrown askew by that proverbial monkey wrench. Examples: George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware (American history, art, black history), Shirley Temple Black and Bill Robinson White (movies), and Amos and Andy (radio). Colescott manipulates familiar situations by weaving in an element of the bizarre. Ethnic illuminations or plays on art are not the point, just the means. How fully he understands the ruinous nature of events, and makes us re-evaluate the excess of lymph material within tradition, truth, and the superhuman state, i.e., the heroic image.

Five years ago, I first encountered Colescott’s Horatian manner—the dialogue, an interaction or exchange between any number of figures. In this case, between his paintings in the Razor Gallery and myself: an unstressed syllable, a foot lacking metric monotony. I was taken by his use of poetry to circumvent sticky situations where questions and answers become synonymous with fighting lovers addressing one another. It’s like realizing the cavalry is not going to come and save you from the stunt people.

I. GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER CROSSING THE DELAWARE

Joe Lewis: There is a Hemingway short story featuring a dialogue between a man and a woman. The woman is about to go to Madrid for an abortion, and several times throughout their conversation she says, “Those hills look like white elephants.” That’s basically it, a story that goes nowhere. They’re waiting for the train and have a couple of drinks, both knowing that they are not dealing with the reality of their situation. They are merely carrying it out, using poetical observations as a distraction. What I’m getting at, Bob, is that like Hemingway you demystify the heroic image by making your characters subservient to the action or deed being portrayed. Your twists, or character substitutions, function in a parallel way to Hemingway’s woman’s, “…those mountains.”

Robert Colescott: I see. What you’re saying is that when I paint George Washington Carver crossing the Delaware, it makes the viewer examine the original action, the real George Washington Carver crossing the Delaware—not to mention black history. In fact, the subtitle of the painting is “Excerpt from a U.S. History Text.”

JL: That painting is a symbol of the true beginnings of America. You’ve transformed a twice familiar cliché into a back-side-of-the-tracks scene of cavorting fishermen. I mean we’re all on that boat: homespun music, cooking, whoredom, corn liquor, le mob provincial.

II. CROW IN THE WHEATFIELD

BC: Why don’t we get on to the Crow, Joe.

JL: Okay, I just hope van Gogh’s not listening. . . .

BC: The actual title of that painting is Auvers-sur-Oise, which refers to where van Gogh died. And then I subtitled it Crow in the Wheatfield. It goes something like this: Here I am doing a painting at the site of Van Gogh’s last painting and his suicide. I represent a spoiled, slightly superficial modern artist who sits in this almost holy place where a great artist took his life and painted maybe his greatest painting. Here I am, a modern man with my little earphones in my ear, the ear that Van Gogh doesn’t have. I’m surrounded by the artifacts—his shoes, the peach trees in bloom, and his dead harlots. And I’m completely oblivious. I’m wearing my shirt that has sunflowers on it. That’s about the depth of my dedication to Van Gogh. And then, what I’m painting is not this landscape, or any thoughts about Van Gogh. . . .

JL: Right. You’re painting the panties.

III. LISTENING TO AMOS AND ANDY

BC: Before your time.

JL: They were white.

BC: Yes, on the radio they were white. Everybody listened to them; well, maybe there were some black people that wouldn’t. There was an undercurrent of “they may be black guys ‘passing’ for white.” An anti–Amos and Andy thing came later. It’s ironic that there were black families out there listening to Amos and Andy and visualizing them as black.

JL: The painting is an ironic period piece. It twists the common role situations, especially in the performing arts of the ’40s and ’50s, in which artists had to assume the stereotype of ignorant nigger to get work. It caused a lot of animosity in the black community. You know that tune, “If you’re black, get back / if you’re brown, stick around / if you’re white, you’re all right.” And after all that, Amos and Andy were played by whites. But, getting back to the painting, it’s funny how you’ve depicted the smiling black mother and son sitting on the sofa— it seems as though they’re trying to get away from the spotlight studio “bubble” that’s invading their living room. It’s really like an Annunciation, where the dove or angel comes through the window to talk with Mary, telling her, “This is the deal, baby. You’ve been chosen.” But what really takes the cake is that the shadow of one of the studio actors has black characteristics, and the hand coming out of the radio speaker is black. Yet, the starry blue sky outside the window gives the whole picture a sense of optimism.

BC: Right. It’s a painting about human weakness, but it’s not a pessimistic painting. It’s about how people believe something that isn’t so, how they’re hypnotized into believing what they want to believe. I think it looks gently at these black human beings, but not so gently at Amos and Andy characters. I made them kind of raunchy looking, but I empathize with the people that are being led down the path by this kind of commercial blackness.

JL: What about the figurines on top of the radio?

BC: It’s one of those pseudo-Greek porcelain white women. It’s really the sculptural equivalent of Maxfield Parrish’s vapid nymphs on swings. The whiteness of the nymph is significant. There were an awful lot of those porcelain figures around at that time.

JL: Is that a roach on the rug or just paint? That may be on my photo here.

BC: No, that’s just ashes from the cigar. He’s dropping ashes on the floor; he’s shitting on them. This hand comes out and, instead of bearing gifts, is dropping cigar ashes. It’s the other end of this Amos and Andy performance.

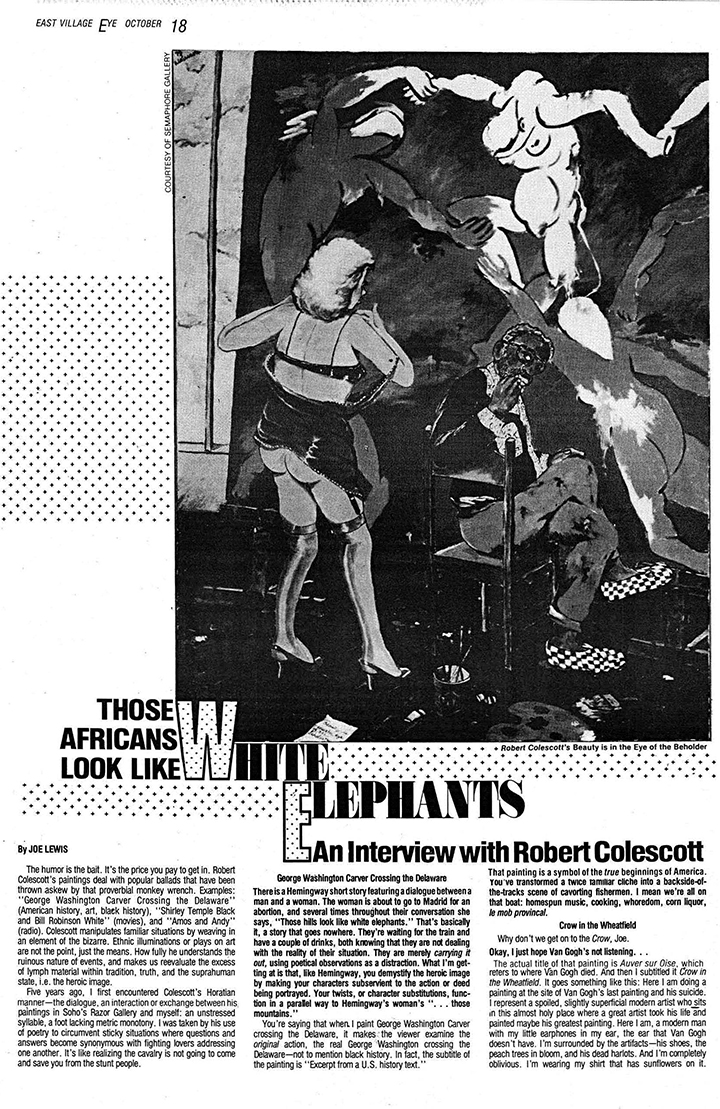

IV. BEAUTY IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

JL: Your work challenges the concept of classical beauty by presenting beauty as a relative issue. For example, your black “Miss America” painting (Miss Liberty). Some of your paintings remind me of Daumier’s burlesque of Gérôme’s Pygmalion, in which the pristine marble figure of Galatea is transformed by the latter artist into a very unclassical woman with midriff bulge. In fact, your painting Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder drives that point home. Here you are sitting in front of Matisse’s Dance, staring contemplatively at the zaftig model who stands in your studio, half-dressed. Not my idea of classical repose.

BC: I think that’s important. I’m involved with these non-flesh-and-blood women that are made of paint and canvas. While painting these dancers as Matisse, I’m also faced with this flesh-and-blood woman. It’s a conflict between art and reality.

JL: Talk about conflict, when you put an Aunt Jemima head on de Kooning’s Woman in I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees DeKoo, that was a shocking juxtaposition. It’s a takeoff on a takeoff (Mel Ramos’s I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill) of de Kooning’s disturbing portrayal of Woman.

BC: I just turned it around. Mel Ramos was saying, “Well, if I were de Kooning, this is the way I would have done it. I still respect action painting, but I’d have to put my little pin-up girl face on there, so some part of me would be on there.” So I thought, well, what if I were de Kooning. I would put Aunt Jemima on there. And besides, maybe she should be on there.

JL: De Kooning’s [Woman] didn’t exactly represent a woman who’s going to look after you. But Aunt Jemima is the epitome of absolute security and safety.

BC: Yes, she’s the stereotyped mammy. The mammy figure is the American descent of the prehistoric Mother Earth goddess.

JL: So far, we’ve discussed your portrayal of a personal type of beauty, as filtered through motifs of Matisse and de Kooning. One of your most recent paintings, Redwood Concerto, deals with yet another concept of beauty: a beauty that exists without a beholder. Like music playing in the forest with no one listening.

BC: Exactly. The woman taking off her clothes in that painting is the concerto in the forest, and she may not even exist except for that little raccoon peering from behind a tree. It’s about alienation and existence too. She’s a woman all by herself doing a striptease.

JL: What about that pair of glasses?

BC: They’re hers. She took off her hat, she took off her jacket, she took off her glasses. The glasses say something about her. Maybe she’s a librarian.

This essay has been edited from the original text produced in 1981 for the first exhibition of Colescott’s work at Semaphore Gallery in New York.