Learn more about the show and each piece here.

Underground Railroad/ Ferrocarril Subterráneo

NO NADA OAXACA

Joe Lewis

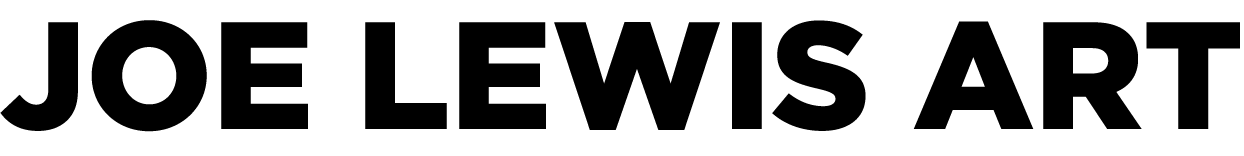

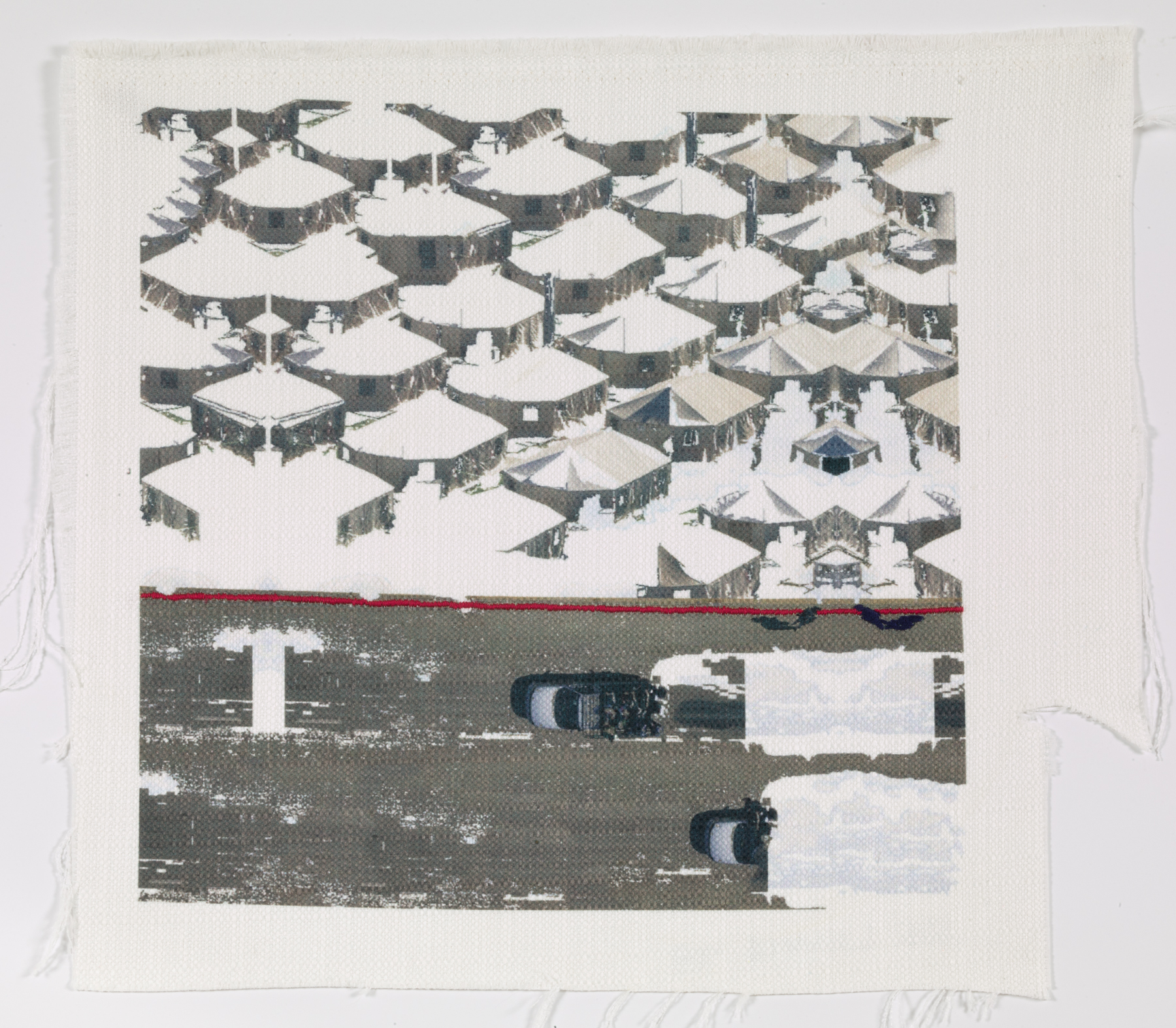

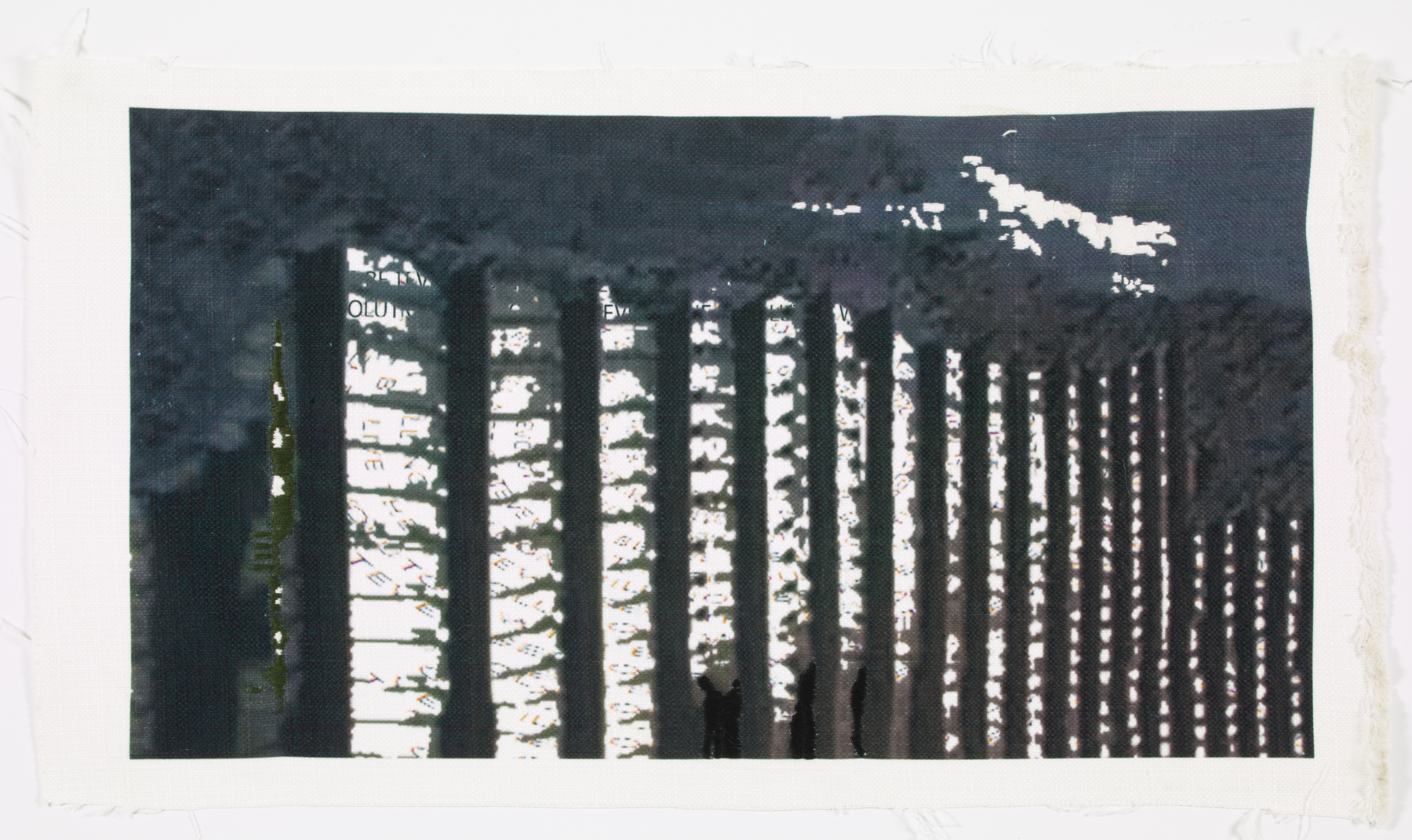

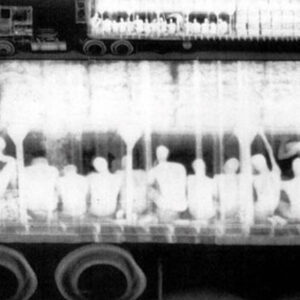

Works for this exhibition were developed from a chance discovery of a few articles in the press about how US custom and border agents were using x-ray technology to detect smuggled people and contraband hidden in trucks and shipping containers. The images posted in one Reuters piece, “Mexico steps up raids on migrant-smuggling trucks, uses giant X-Ray,” [1] were very disturbing and reminded me of images portraying the physical distribution of African slaves in slave ship cargo holes.

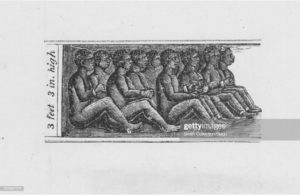

The following image, found in a collection of slave ship engravings, bore an eerie resemblance to the pictures of people hidden in trucks revealed by x-ray machines.

The Underground Railroad was a system of secret routes and safe houses that dotted the American landscape in the 19th-century, used by those of African descent fleeing North to free states or Canada to escape bondage. In Texas, the Underground Railroad ran south into Mexico, which had abolished slavery in 1829, and allowed runaway slaves and indigenous peoples into their country, refusing to send either group back to the Texas territories; and protecting them from slave hunters. Numerous border towns along the Rio Grande River, especially in the state of Coahuila, Piedras Negras, San Fernando de Rosas (present-day Zaragoza), Ciudad Acuña, and Nuevo Laredo became first destinations for runaway slaves.

Modern-day relationships between the smuggler and the smuggled are not precisely the same as those between the runaway slaves, their owners, and slave hunters. Still, the contemporary economic realities of the former – menial labor, living in challenging urban and rural environments, lack of legal protection in an underground commercial subculture, etc., have distinct similarities. For example, human trafficking or continuously forced servitude to the cartels have a symbiotic, if not direct, relationship to the historical nature of indenture.

The irony of this story is that human traffickers and smugglers may now be using the same routes to bring people and contraband into the United States that runaway slaves and indigenous peoples used to escape into Mexico. The connection between these cultures, their struggles for self-determination, cultural equity, and justice, past and present, continue unabated.

[2] https://molloy.libguides.com/c.php?g=58165&p=2791600 View of chained African slaves in the cargo hold of a slave ship, measuring three feet and three inches high.

Underground Railroad/ Ferrocarril Subterráneo

NO NADA OAXACA

Joe Lewis (Spanish version by Isaac D Scherson)

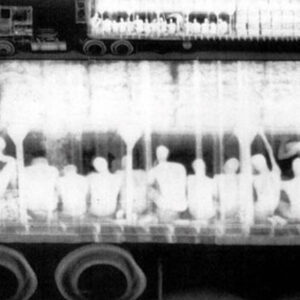

“Underground Railroad/ Ferrocarril Subterráneo;” trabajos para esta muestra artística fueron desarrollados a partir de un descubrimiento fortuito de algunos artículos de la prensa sobre como agentes de frontera y aduanas de EE. UU. usan rayos X para detectar contrabando y tráfico de ilegales escondidos en camiones y/o contenedores. Las imágenes de un artículo de Reuters, “Mexico steps up raids on migrant-smuggling trucks, uses giant X-Ray [1] me perturbaron particularmente y me recordaron las imágenes de la distribución física de esclavos africanos en las galeras de barcos.

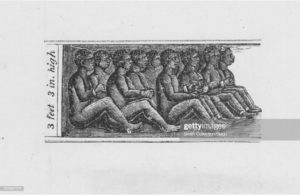

La siguiente imagen, de una colección de grabados de barcos de esclavos, tienen una impresionante semblanza con las fotos de las máquinas gigantes de rayos X de gente escondida en camiones en la frontera con EE. UU.

The Underground Railroad/Ferrocarril Subterráneo fue un sistema de rutas y casas secretas punteadas en el paisaje americano durante el siglo 19: fueron usadas por aquellos de origen africano escapando la esclavitud a estados libres del Norte y/o a Canadá. En Texas, el Ferrocarril Subterráneo se extendió al sur hasta México, que había abolido la esclavitud en 1829 y aceptaba en el país a esclavos fugitivos y a indígenas, rechazando cualquier demanda de devolución y/o extradición a territorios Tejanos, protegiéndolos así de los cazadores de esclavos. Varias ciudades fronterizas a lo largo del Río Grande, especialmente en el estado de Coahuila; Piedras Negras, San Fernando de Rosas (hoy Zaragoza), Ciudad Acuña, y Nuevo Laredo se convirtieron en un destino preferido de los esclavos escapados.

Las relaciones actuales entre el contrabandista y los ilegales no son las mismas que aquellas entre los esclavos y los dueños y/o los cazadores de esclavos. Sin embargo, las realidades económicas contemporáneas de ilegales – braceros viviendo en sectores desfavorecidos, urbanos o rurales – son sorprendentemente similares en la desprotección legal de esta subcultura comercial prácticamente secreta. Por ejemplo, el tráfico humano o el servilismo forzado a los carteles tienen una relación simbiótica, si no directa, a la naturaleza histórica del contrato esclavista.

La ironía de esta historia es que los traficantes contrabandistas de humanos usan, hoy por hoy, probablemente las mismas rutas para traficar gente y contrabando a los EE. UU. que usaron los indígenas y los esclavos fugitivos para encontrar la libertad en México. La relación conectiva entre estas culturas, sus luchas por la auto determinación, la igualdad cultural, la justicia, pasada y presente, continúan sin cesar y sin desafío.

[2] https://molloy.libguides.com/c.php?g=58165&p=2791600 View of chained African slaves in the cargo hold of a slave ship, measuring three feet and three inches high.